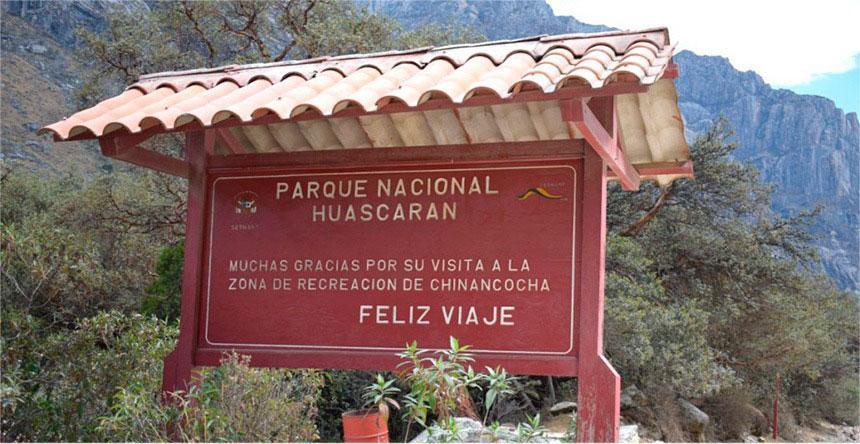

The Huascarán National Park, established as a protected area on July 1, 1975, and later designated as a biosphere reserve in 1977 and as a Natural Heritage of Humanity in 1985, is located in the Peruvian department of Áncash. It is recognized for hosting within its expanse 20 towering snow-capped peaks that surpass 6000 meters above sea level, including Peru’s and the entire Intertropical Region’s highest mountain: the mighty Huascarán snow massif, from which the park takes its name.

Content

Description of Huascarán National Park

Huascarán National Park, declared a Natural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, is a refuge of biodiversity and natural beauty. This park is home to the Cordillera Blanca, the world’s highest tropical mountain range, and offers a variety of ecosystems ranging from lush cloud forests to mighty glaciers.

Ecological and Cultural Importance

This park is not only a sanctuary for countless species of flora and fauna, some of them endemic to Peru, but also preserves areas of great cultural significance for indigenous communities. The relationship between man and nature has been woven here over millennia, offering a unique perspective on sustainability and coexistence.

Huascarán Region

The Huascarán region has been inhabited since ancient times, with evidence dating back to 12,560 BCE, with the Cave of the Guitarrero being one of the oldest settlements in Peru. Over time, sedentary communities emerged whose social, political, and religious structures were closely linked to nature, being influenced by cultures such as Chavín, Recuay, and Inca.

During the era of Spanish conquest and colonization between 1532 and 1600, the region was divided into encomiendas, such as Huaylas and Conchucos, with the purpose of exploiting its mineral resources, mainly gold and silver. This economic activity thrived for about four centuries until the park area was designated as a protected natural space, limiting economic activities only to those that directly benefited local peasant communities.

Starting from the 1860s, scientific expeditions began to study the Cordillera Blanca and its surroundings. Researchers like Antonio Raymondi and other European and North American scientists were pioneers in exploring the heights, being the first to reach the summits of the mighty Huascarán snow massif and other mountains that exceed 6000 meters above sea level.

In 1977, UNESCO recognized Huascarán National Park as a biosphere reserve, and in 1985, it was declared a Natural Heritage of Humanity. Since then, its management was transferred to the National Service of Natural Protected Areas by the State. With an extension of 3400 km², the park harbors a wide variety of ecosystems, lagoons, glaciers, and rich biodiversity, making it one of the country’s most important parks in terms of hydrological potential and nature conservation. It offers various recreational activities such as mountaineering, camping, boating, and wildlife viewing, also hosting international sports events like the Downhill Skateboarding World Circuit since 2017.

History

Establishment of Huascarán National Park

The history of Huascarán National Park dates back to the 1960s when Senator Augusto Guzmán Robles presented a bill for its creation. In 1963, two years after the establishment of the Manu National Park, the Forestry and Hunting Service delimited the park area for the first time, initially called Cordillera Blanca National Park, but renamed as the Huascarán National Park Board in 1966. This initial area covered 321,000 hectares, and a Ministerial Resolution was issued prohibiting logging and hunting of native species.

On July 1, 1975, the Peruvian government officially created Huascarán National Park by Supreme Decree, expanding its final extension to 340,000 hectares. In March 1977, UNESCO recognized it as a biosphere reserve, including the park’s core, buffer zone, and transition zone, covering various towns and rural settlements, with a total area of 1,115,800 hectares, equivalent to 30% of the departmental territory.

Finally, on December 14, 1985, Huascarán National Park was declared a Natural Heritage of Humanity. Organizations like Birdlife International and Conservation International have recognized the park’s core and other areas within the reserve as important for bird conservation due to their high endemism and the threats they face.

In 2004, the park administration was transferred to the newly created National Service of Natural Protected Areas by the State (SERNANP). Since then, efforts have been made to protect the park and its buffer zone, preserving a wide range of habitats, natural species, and numerous archaeological sites.

Evolution and Changes Over the Years

Since its foundation, Huascarán National Park has undergone numerous changes, adapting to the challenges of modern conservation and evolving to enhance visitor experiences without compromising its ecological integrity.

The Legacy of Huascarán National Park

Located in Peru, Huascarán National Park takes its name from the mighty Huascarán mountain, the highest peak in the Cordillera Blanca and the entire Intertropical Region. The term "Huascarán" comes from the Ancash Quechua "waska," meaning ‘rope or lasso,’ and "ran," which is a verbal or adverbial suffix. Therefore, "Huascarán" can be interpreted as ‘arranged like a rope’ or, more contextually, as a ‘chain of mountains.’ This national park is renowned for its breathtaking natural beauty and its importance in biodiversity conservation in the region.

History of the Huascarán Region

During the division of the supercontinent Pangaea, the eastern territory of the current Andes mountain range —at that time a plateau with peaks reaching a thousand meters— was an immense and dense savanna that bordered a sea that extended from present-day Colombia to northern Bolivia. This temperate ecosystem by the sea with tributary rivers of great flow descending from the primordial Andes mountain range favored the proliferation of diverse species of dinosaurs, which left an extensive deposit of footprints and fossils in the current southeastern territory of the national park, in lands that formed during the Albian stage of the Lower Cretaceous and are now located above 4000 meters above sea level.

Pre-Columbian Era

Human presence in the region dates back to approximately 13,000 BCE. Within and around the park, there are several archaeological sites showing that occupations at altitudes higher than 3700 meters above sea level were quite common in their time. The most well-known remains are Guitarrero, La Galgada, Tumshucaico (Caraz), Huaricoto (Marcará), Honko Pampa, Ichic Tiog (Chacas), and Chavín de Huántar. For thousands of years, inhabitants from both sides crossed the Cordillera Blanca through the Santa Cruz-Huaripampa, Llanganuco-Morococha, Honda-Juitush, Uquian-Ututo-Shongo, and Olleros-Chavín gorges. On the flanks of the mountain range and in several of its gorges, there are remnants of large extensions of agricultural terraces and ancient corrals. Cultivation and pasture areas were supplied with water provided by ingenious dam and canal systems.

Viceroyalty and Republic

During the Viceroyalty, the park’s territory was acquired by wealthy Portuguese, Spanish, and Creole families, generally military personnel who had distinguished themselves in Europe or America. These families founded large estates to exploit the adjacent mineral-rich territory. Mining continued uninterrupted for four hundred years and would consolidate with the arrival of the Republic. The lands initially belonging to peasant communities were completely seized from them, leading to numerous complaints from indigenous inhabitants against the landowners, who installed gates and overseers at the entrances to the various gorges, claiming access to forests for firewood, pasture, and other natural resources in the highlands.

Huascarán Explorers

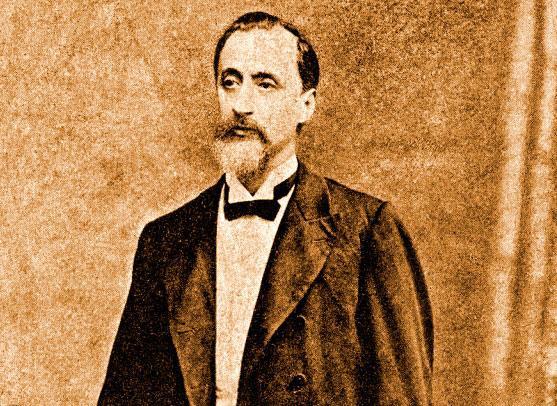

In the 1860s, the Italian scientist Antonio Raimondi conducted the first detailed study of the region’s geology, documented in his book "El departamento de Áncash y sus riquezas minerales" published in 1873. In this work, Raimondi also included observations on the biological and archaeological richness of the Callejón de Huaylas and the Conchucos area.

Subsequently, between 1880 and 1900, German scientists such as Gustav Steinmann, August Weberbauer, and Wilhelm Sievers carried out more detailed studies within the Cordillera Blanca. Simultaneously, the Frenchman A. C. de Carmand expanded Raimondi’s observations on mineral deposits in the region.

In 1904, Reginald Enock, an English engineer, attempted to climb Huascarán, reaching an altitude of 5100 meters. In 1908, the American Annie Peck led the first successful expedition to the summit of the north peak of Huascarán, accompanied by two Swiss guides, after several failed attempts in previous years.

In 1932, members of the Austro-German Alpine Club began scientific expeditions in the Cordillera Blanca, achieving the first ascent of Huascarán Sur. These expeditions, which continued until 1938, conquered several significant peaks in the region.

In 1950, cartographer Fritz Ebster succeeded in representing the entire Cordillera Blanca on a single map for the first time. Additionally, Hans Kinzl led several expeditions in the following decades, continuing the study of the snow-capped peaks, glaciers, and lagoons of the region.

In 1984, American botanist David Smith conducted a census of the mountainous flora, recording 799 species within Huascarán National Park.

Geography

Huascarán National Park is located in the central highlands of Peru, within the department of Áncash. It is completely aligned with the Cordillera Negra and encompasses the Suni and Janca biogeographic regions, covering the entire extent of the Cordillera Blanca. From a political perspective, the park extends through parts of the provinces of Bolognesi, Asunción, Carhuaz, Huaraz, Huari, Huaylas, Mariscal Luzuriaga, Pomabamba, Recuay, and Yungay. With a total area of 3400 km² (or 340,000 hectares), the park has approximate dimensions of 158 km in length from north to south and 34 km from east to west. Its perimeter is delimited by 110 markers in UTM coordinates.

Location and Extension

Located in the Ancash region, the park covers an area of over 340,000 hectares, protecting vast segments of the Cordillera Blanca.

- Administration: SERNANP.

- Protection level: National park.

- Creation date: July 1, 1975.

- Number of localities: 10 provinces.

- Visitors (2016): 259,090.

- Surface area: 340,000 ha.

Main Geographic Features: Cordillera Blanca, Callejón de Huaylas Valley

The Cordillera Blanca, located within Huascarán National Park, stretches for approximately 180 km from north to south. It is home to an impressive array of natural resources, including 663 glaciers, 16 snow-capped peaks surpassing 6000 meters above sea level, and another 17 exceeding 5000 meters above sea level. Additionally, the region boasts more than 269 lagoons and 41 rivers that feed into the Santa and Marañón rivers.

The Callejón de Huaylas Valley is a picturesque region located in the central part of the Peruvian Andes. Surrounded by towering mountains of the Cordillera Blanca and the Cordillera Negra, this valley offers stunning landscapes and rich biodiversity along approximately 180 km from north to south, providing breathtaking panoramic views of snow-capped peaks and natural landscapes of great beauty. In addition to its spectacular natural environment, the valley is home to charming Andean towns such as Carhuaz and Caraz, which preserve their rich culture and ancestral traditions. The Callejón de Huaylas Valley is a must-visit destination for nature lovers and adventure tourism enthusiasts, offering a variety of activities such as hiking, rock climbing, and mountaineering.

The Impressive Relief of Huascarán National Park

The relief of Huascarán National Park is extremely rugged, encompassing the entire Cordillera Blanca with its eastern flanks in the Conchucos region and western flanks in the Callejón de Huaylas. It is characterized by its imposing snow-capped peaks, with altitudes ranging from 5300 to 6757 meters above sea level, with Huascarán Sur being the highest in Peru and the entire Intertropical Region.

Deep and steep gorges traverse the Cordillera Blanca transversely, presenting extremely steep slopes with gradients ranging from 85% to 90%. Towards the south of the park, these slopes decrease, with slopes ranging from 30% to 60%. The width of these depressions varies between 200 and 400 meters, and some are occupied by extensive lagoons such as Llanganuco, Parón, and Rajucolta, formed as a result of deglaciation.

The landscape below 5000 meters above sea level is characterized by a mixture of small and large pampas surrounded by semi-steep terrain. These pampas, of fluvio-alluvial origin, are mainly composed of clayey sand. Above 5000 meters, there are lateral moraines formed by deglaciation, as well as rubble cones flanked by very steep terrain, in some places completely vertical.

The geology of Huascarán National Park and the Contrahierbas massif in the Cordillera Blanca is distinguished by its composition of andesitic volcanic rock, which gives it its characteristic black color. Local inhabitants call it Yanarraju in Quechua, which means "black mountain". The park area encompasses geological formations ranging from the Upper Jurassic to the recent Quaternary, composed of a variety of sedimentary, volcanic, intrusive rocks, and Quaternary deposits. Local geology also exhibits structural features such as folds and faults, like the notable Cordillera Blanca Fault, which forms the batholith of the same name.

The geological structures in the area are very complex due to strong deformations and faults that occurred during the Andean orogeny and subsequent processes of emplacement of the Cordillera Blanca batholith, as well as the spirogenic movement that affected the Andes in general. The present sedimentary rocks show several folds, mainly oriented in the northwest-southeast direction, in line with the orientation of the Andes, and are intersected by faults of different magnitudes.

In the heart of the park, 15 geological formations have been identified, with the most notable being the Granodiorite Tonalite, covering 24.6% of the territory, the Chicama Formation with 22.8%, and various glacial, moraine, and fluvioglacial deposits covering 19.8%, 10.2%, and 7.8% of the area respectively.

Cordillera Blanca Fault

The active Cordillera Blanca Fault, which extends approximately 200 km, marks the western boundary of the Cordillera Blanca Batholith, from Conococha in the south to Corongo in the north. It formed during the boundary between the Neogene and the Quaternary, about 5.3 million years ago, when the uplift of the Andes began. During the Quaternary period, about 2.5 million years ago, when this region was a plateau with altitudes not exceeding 1000 m, the fault’s activity intensified, causing a subsidence of the western block (the Callejón de Huaylas) and an uplift of the eastern block (the eastern range of Áncash), which rose about 3000 meters at a rate of approximately 1 mm per year, a rate that continues today.

Seismic geology studies indicate that this fault remains active, making it an important seismic source within the continent or intraplate. This means that violent ruptures with geological displacements of up to 3 meters can occur, resulting in earthquakes with magnitudes of up to 7.4.

Hydrography

Glaciers

Glaciers extend along its 180 kilometers, from the Tuco peak in the south to the vicinity of the Champará peak in the north. There are about 27 glaciers that reach altitudes above 6000 meters above sea level, and approximately 200 more that are between 5000 and 6000 meters. Most of the rivers originating in the valleys of this mountain range flow into the Santa River basin. The snow-covered area covers 504.4 km², equivalent to 14.84% of the total park area. In total, there are estimated to be 712 glaciers covering 486,037 km² and an approximate volume of 18,458 km³ of water in solid state, which possess significant hydrological potential.

Biodiversity

Flora: Endemic Species and Their Importance

The park harbors a rich variety of flora, including endemic species that are essential for ecological balance and the conservation of soil and water.

Fauna: Species Diversity and Conservation

The diversity of fauna is notable, with species such as the Andean condor, the puma, and the taruca finding refuge in this protected habitat.

Ecosystems: Páramo, Cloud Forests, Glaciers

The different ecosystems, from páramos to cloud forests and glaciers, create a mosaic of habitats that sustain exceptional biodiversity.

Main Attractions

Summit of Huascarán

The summit of Huascarán, the highest point in Peru, offers spectacular views and is a coveted challenge for mountaineers from around the world.

Lakes: Llanganuco, 69, Parón, among others

The park’s lakes, such as Llanganuco, 69, and Parón, are famous for their crystal-clear waters and the stunning landscapes that surround them.

Traditional Villages and Cultural Tourism

The villages around the park offer a rich cultural experience, with vibrant traditions and hospitality that warms the hearts of visitors.

Tourist Activities

Hiking and Trekking: Santa Cruz Route, Laguna 69

Hiking and trekking routes, such as the Santa Cruz and Laguna 69, are perfect for exploring the park’s natural diversity on foot.

Ice Climbing and Mountaineering

For adventurers, ice climbing and mountaineering on the park’s snowy peaks represent unforgettable challenges.

Flora and Fauna Observation

Observing the rich flora and fauna of the park is a peaceful activity that allows visitors to deeply connect with nature.